Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

by Lois Beckett ProPublica, Oct. 14, 2011, 12:41 p.m.

By the end of this year, the State Department will decide whether to give a Canadian company permission to construct a 1,700-mile, $7 billion pipeline that would transport crude oil from Canada to refineries in Texas.

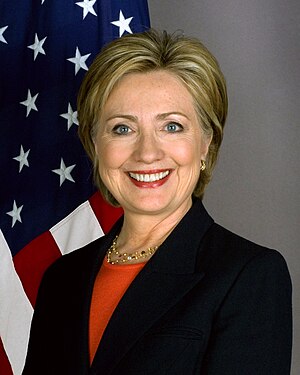

The project has sparked major environmental concerns, particularly in Nebraska, where the pipeline would pass over an aquifer that provides drinking water and irrigation to much of the Midwest. It has also drawn scrutiny because of the company's political connections and conflicts of interest. A key lobbyist for TransCanada, which would build the pipeline, also worked for Secretary of State Hillary Clinton [1] on her presidential campaign. And the company that conducted the project's environmental impact report had financial ties to TransCanada.

The debate over the pipeline is both complicated and fierce [2], and it crosses party lines, with much sparring over the potential environmental and economic impacts of the project. More than 1,000 arrests were made during protests of the pipeline [3] last summer in Washington, D.C.

Here's our breakdown of the controversy, including the benefits and risks of the project, and the concerns about the State Department's role.

Potential benefits — energy security and jobs for Americans — and how they're disputed

Proponents of the project point to two main benefits for Americans. First, it would improve America's energy security [4], because it would bring in more oil from friendly Canada and reduce our dependence on volatile countries in South America and the Middle East. Secondly, the pipeline would create well-paying construction jobs and provide a broader economic boost to the American economy. Labor unions have supported the project [5].

TransCanada estimates that the project would directly create 20,000 construction and manufacturing jobs for Americans [6]. A study paid for by TransCanada [7] also estimated the economic impact over the life of the pipeline at about $20 billion in total spending.

But a report by Cornell University's Global Labor Institute [8] questioned those numbers, noting that the project would "create no more than 2,500-4,650 temporary direct construction jobs for two years, according to TransCanada's own data supplied to the State Department."

Critics of the project have also questioned whether the pipeline's oil, once processed in American refineries on the Gulf Coast, would actually be sold to Americans rather than being exported for sale elsewhere [9]. As a New York Times editorial opposing the pipeline noted, five of the six companies [9] that have already contracted for much of the pipeline's oil are foreign companies — and the sixth focuses on exporting oil.

The Washington Post, which editorialized in favor of the pipeline [4], said this should not be a major objection. "The bottom line remains: The more American refineries source their low-grade crude via pipeline from Canada and not from tankers out of the Middle East or Venezuela, the better, even if not every refined barrel stays in the country," the Post editorial stated.

Cozy relationships with the State Department — and a compromised environmental report

Because the project crosses the U.S. border, it requires a permit from the State Department. As part of that process, the State Department did an environmental impact report [10]. The study concluded that, if operated correctly, the pipeline would have "limited adverse environmental impacts." But a New York Times investigation found that the company that the government hired to conduct the study had significant financial ties to TransCanada [11] — and that this conflict of interest "flouted the intent of a federal law" requiring federal agencies to select contractors that have no potential interest in the outcome of the project being evaluated.

Environmental groups have also scrutinized the relationship between State Department officials and TransCanada's representative in Washington. Paul Elliott, who worked on Hillary Clinton's presidential campaign, was actively lobbying the State Department and Congress [12] about the project for a year and a half before he officially registered as a lobbyist, according to State Department email messages made public by the environmental group Friends of the Earth [13]. Elliott did not comment on the emails, but a TransCanada spokesperson said he was simply doing his job as a lobbyist.

The emails showed a friendly relationship between Elliott and his State Department contact, who wrote "Go Paul!" [12] when Elliott secured the support of a key congressman for the Keystone project.

The State Department has said that it will consider the merits of the pipeline proposal impartially [2].

As the news organization Mother Jones pointed out [12], the emails also revealed "an apparent understanding between the State Department and TransCanada that the company would later seek to raise the pressure used to pump oil through the pipeline — even though the company said publicly it would do the opposite [14]."

TransCanada had originally sought permission to use a higher-than-usual pressure in its pipeline [15] but publicly backed away from the request in response to the concerns of citizens and politicians that higher pressure might increase the risk of leaks and environmental damage.

A WikiLeaks cable also revealed that a different U.S. diplomat had given PR tips to Canadian officials about the project. As the Los Angeles Times noted, the diplomat "had instructed them in improving 'oil sands messaging,' [16] including 'increasing visibility and accessibility of more positive news stories.'"

Concerns about water contamination across the Great Plains

The proposed route of the pipeline passes over the Sandhills wetland of Nebraska — and over the most important aquifer in the nation, the Ogallala Aquifer, which provides drinking water and irrigation to a large swathe of Midwestern states [17].

This has prompted opposition from Nebraska politicians. The state's Republican governor wrote a letter [18] to President Obama asking him not to approve the project, and state legislators are considering legislation [19] limiting where the pipeline can be located.

"Clearly, the contamination of groundwater is the top concern," State Sen. Mike Flood told reporters [20].

Opposition to the pipeline is so broad in Nebraska [21] that a TransCanada-sponsored video that was perceived as supporting the pipeline was booed at a University of Nebraska football game [22], which resulted in the Cornhuskers athletic department ending a TransCanada sponsorship deal [22].

But at least one scientist with significant experience with the Ogallala Aquifer said fears about contamination from the pipeline are overblown [23].

James Goeke, a hydrogeologist and professor emeritus [24] at the University of Nebraska, wrote on The New York Times' website that the geography of the aquifer — there'd be clay between the pipeline and the water, and much of the aquifer is uphill from the pipeline's proposed location — means that a leak in the pipeline "would pose a minimal risk to the aquifer as a whole." He suggested the government "require TransCanada to post a bond for any cleanup in the event of a spill," and noted that in particularly vulnerable areas, TransCanada has promised to encase the pipeline in cement.

Leaks and spills

The Keystone XL pipeline would carry a diluted form of tar sands, a type of natural petroleum deposit. Environmentalists argue that the tar sands, or "dilbit," mixture that the pipeline would transport [25] is more corrosive than typical crude oil, and thus might cause more leaks in the pipeline.

These fears were heightened by an oil spill in Michigan [26] that leaked roughly 800,000 gallons of tar sands into Michigan's Kalamazoo River in July 2010. The spill came within 80 miles of Lake Michigan, and a year later, the Environmental Protection Agency has ordered Enbridge, the energy company responsible for the spill, to conduct further cleanup, citing pockets of submerged oil covering about 200 acres [27] of the river's path.

The Christian Science Monitor has a good, brief summary of spills [3] on TransCanada's existing U.S. pipeline, and notes that according to the State Department estimate, "the maximum the Keystone XL could potentially spill would be 2.8 million gallons along an area of 1.7 miles [3]."

Concerns about eminent domain

Some property owners whose land the pipeline would cross have spoken out against the company's approach [2], particularly the fact that a Canadian company is able to use eminent domain to acquire the use of private land.

The issue has struck a nerve across the political spectrum and has helped bring together Tea Party and environmental activists in Texas [28] to oppose the project.

TransCanada says it is compensating landowners fairly, and notes that, "Our permit does allow us to use eminent domain [6] to acquire an easement and provide compensation for the landowner. Keystone XL always prefers to avoid the use of eminent domain, and if we cannot reach an agreement, then we turn to the independent processes/hearings that are established in Texas and other U.S. states."

Broader environmental concerns

Environmentalists also object not just to the pipeline itself but to the start-to-finish process of refining tar sands, which has a heavy impact on the environment, including global warming. As a Stanford University professor wrote [29] on The New York Times' website:

Available evidence suggests that oil sands, on a "well-to-wheels" basis, have 15 to 20 percent higher greenhouse emissions than conventional oil. This is because of increased energy demand during extraction and the use of high-carbon fuels like petroleum coke. Also, water pollution concerns plague mining-based projects that produce large volumes of tailings (a contaminated, watery waste product).Critics of the project [8] argue that approving Keystone XL could have a "chilling effect" on efforts to create green jobs, and that it would demonstrate that the U.S. is not serious about its climate change leadership — and that Canada is not serious about trying to reach its Kyoto targets.

But as many have noted, denying approval to Keystone XL wouldn't stop tar sands production. As the Heritage Foundation's David Kreutzer argued [30]: "Block the XL pipeline if you think the environment will be better served by shipping Canadian oil an extra 6,000 miles across the Pacific in oil-consuming super tankers and then refining it in less-regulated Chinese refineries."

No comments:

Post a Comment